Finally, Malaysians could enjoy berbuka puasa (breaking of fast) by having a sumptuous meal with their loved ones without limitation on the number of people gathering together and social distancing during this Ramadan month after two years of the pandemic. However, the rising food price inflation continues to pose challenges, especially among low-income households who are still trying to recover their economic livelihoods during this endemic period.

Although the government has extended the Keluarga Malaysia Sales Programme (PJKM) till June to reduce the financial burden of the rakyat, vegetables remain one of the most nutritious food items experiencing soaring prices.

According to the Consumer Association of Penang (CAP)’s statement in November 2021, the price for red chillies had gone up from RM13 to RM19 per kilogramme (kg) and RM14 for green chillies from RM10 per kg previously.

When we consider the vegetable price reduction by 20% under the PJKM scheme, the price for red and green chillies per kg should be RM15.20 and RM11.20, respectively.

However, when we look at the retail price from the Federal Agricultural Marketing Authority (FAMA), the average pricing of red and green chillies in Seberang Perai Tengah, Penang yesterday (April 7, 2022) is at RM18 and RM12 per kg, respectively.

The increasing price trend indicates that consumers had to spend more money buying the same amount of chillies, a common ingredient to cook curry.

Therefore, there is an increasing concern that Malaysians with low-income levels will be forced to “downgrade” by purchasing cheaper food such as bread and instant noodles to mitigate the impact on their purchasing power and what little savings are left.

With reduced income, the bottom 40% (B40) have to lower their food intake. They are relatively less capable of buying healthy food relative to the pre-pandemic era.

Nonetheless, the increase in Producer Price Index (PPI) and Consumer Price Index (CPI) show that rising food price inflation will not subside anytime soon.

The Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM) revealed in its latest findings that PPI for local production – an output-based index that measures the average change in commodity prices for local market sales valued at factory prices – has increased from 9.2% in January 2022 to 9.7% in February 2022. Higher primary commodity prices have increased PPI.

The manufacturing index has experienced a 7.9% increase in February 2022 compared to 7.0% in January 2022. The sub-manufacturing index for the manufacture of vegetable & animal oils & fats is the second-highest contributor to the overall manufacturing index, at 18.6%. The manufacture of refined petroleum products witnessed a 20.3% increase, followed by the manufacture of basic chemicals, fertilisers & nitrogen compounds, and plastics & synthetic rubber in primary forms (13.1%).

In a month-on-month comparison, the PPI for local production has increased to 2%, compared to 1.3% in January 2022. Among all manufacturing subsectors, the manufacture of vegetable & animal oils & fats witnessed a 3.2% increase, followed by the manufacture of refined petroleum products (2.1%) and the manufacture of electronic components & boards (0.5%). As a result, the manufacturing index on a month-on-month basis rose from 0.8% in January 2022 to 1.3% in February 2022.

On the other hand, the CPI increased moderately by 2.2% – from 122.5 in February 2021 to 125.2 in February 2022.

A rise in food inflation is the main attribute to the CPI increase.

Chief Statistician Datuk Seri Mohd Uzir Mahidin indicated that the 3.7% increase in the Food & Non-Alcoholic Beverages category was mainly due to the rise in the sub-category of “food at home” by 4.1% over the same period. Nevertheless, he did not mention vegetables are the essential stuff used for cooking preparation at home.

On the other hand, the other sub-category, namely “food away from home”, increased from 3.1% in January 2022 to 3.6% in February 2022. The relaxation of Covid-19 related standard operating procedures (SOPs) has resulted in more Malaysians eating out once again, among other social activities.

No doubt meat items such as cooked beef (6.4%), murtabak (6.2%) and satay (5.4%) are contributing the most to the increase in the “food away from home” index. Yet, vegetables (4.3%) consist of a certain proportion of the index asides from milk, cheese & eggs (5.1%) and fish & seafood (3.6%).

The CPI “food away from home” sub-index shows that Malaysians, in general, are placing a balanced and healthy diet as their priority.

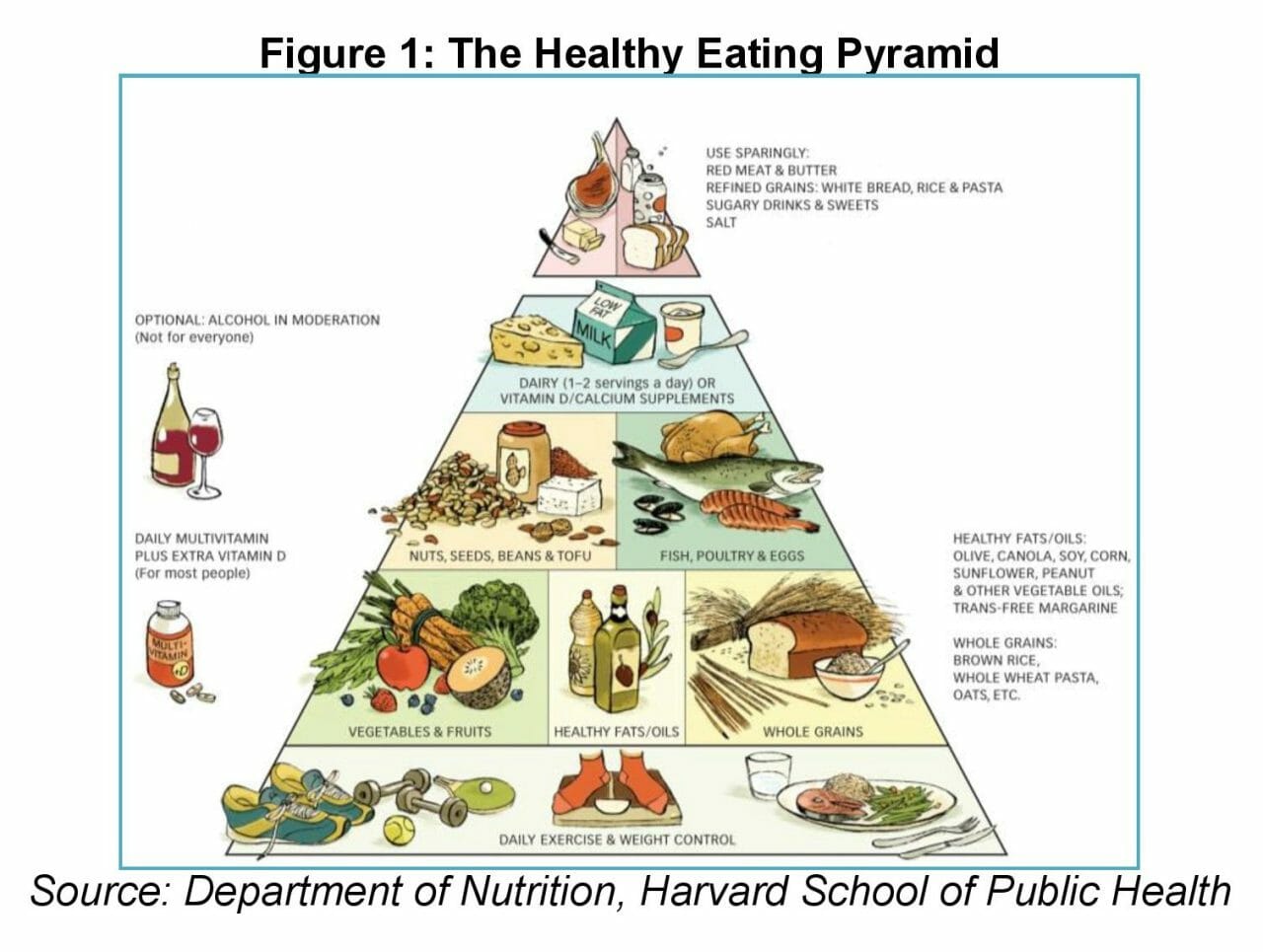

We could also refer to “The Healthy Eating Pyramid” published by the Department of Nutrition, Harvard School of Public Health, as shown in Figure 1.

In short, a balanced and healthy diet consists of different kinds of food in a certain amount of quantities and proportions so that the requirement for calories, proteins, minerals, vitamins and alternative nutrients are deemed adequate.

Statistics seem to show that most Malaysians have balanced meals comprising meat, vegetable and dairy intake.

While a Malaysian newborn in 2019 can expect to live up to 75 years, compared to 71.9 years in 1990, 9.5 of those years are likely to be spent in poor health – 0.4 years more than in 1990. “Social determinants of health” (SDOH) such as housing, education, jobs, incomes, access to nutritious food and physical activity, for instance, could be the leading factors to poor health.

Therefore, those with limited access to nutritious food have a higher risk of being diagnosed with non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as diabetes, obesity and heart disease.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO)’s 2018 data, coronary heart disease-related deaths in Malaysia reached 34,766 or 24.69% of total deaths.

Imagine those B40 communities who lost their jobs or income during the pandemic: how could they afford to buy increasingly expensive vegetables for their nutritional intake?

With soaring vegetable prices, food truck and coffee shop owners, among others, with limited cash flow only could cut the vegetable portions served in order to reduce associated operating costs ranging from salaries of employees, rent, utility charges and cooking gas.

- Here’s what the government could do; work closely with several non-governmental organisations (NGOs) such as Food Aid Foundation, The Lost Food Project and Pasar Grub, distributing leftover but consumable food or “lower quality” vegetables and fruits to the B40 communities who are most vulnerable to food insecurity.

To ease the food aid delivery, the government should mark and map and include all the B40 families onto their geographic information system (GIS) for data collection, planning and implementation, especially those who are living in interior and squatter areas;

- Integrate food and nutrition-focused programmes with different transfer modalities such as in-kind, cash or vouchers into the social protection system.

Low-income households, in particular, can use food vouchers or cash to buy food. It would ensure everyone has a basic income, giving them the ability to cover their basic spending needs and enjoy nutritious food;

- Provide subsidies for seeds, fertilisers and pesticides to be paid directly to the farmers through a coupon system.

The farmer could use the coupon to buy high-quality seeds from any vendor or company. The vendor also can use the coupon to claim payment from the government. This approach would create healthy competition among vendors besides stimulating agricultural activities. At the same time, it would motivate farmers to produce high-quality vegetables with sufficient quantities for domestic needs, allowing Malaysia to be less dependent on imports; and

- FAMA and related government agencies should do more in terms of logistics by assisting rural farmers to store and transport agricultural products to major cities of Malaysia. So, the rural farmers no longer have to travel across muddy, rocky roads, selling vegetables to the end-users.

In a nutshell, the government has to intensify and enhance the policy mechanisms to guarantee the welfare of farmers, wholesalers, retailers and consumers alike.

The price ceiling (maximum price) or price control mechanism that is targeted only at the retailer, i.e., market vegetable seller, is not sufficient to counterbalance the effects of rising food price inflation.

As such, the government must take pro-active measures to address the issue of profiteering by focusing on the middlemen in the supply chain who dominate and fix the prices, as even confirmed through investigations by consumer groups, for example.

Both the Ministry of Domestic Trade and Consumer Affairs Malaysia (KPDNHEP) and FAMA are the responsible government stakeholders to conduct regular monitoring and enforcement – ensuring farm, wholesale and retail prices are set at reasonable and acceptable levels.

Amanda Yeo is Research Analyst at EMIR Research, an independent think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.