By: Prof. Dr. Mohammad Tariqur Rahman

Parallel to the unstoppable dynamics of civilization, global development follows UN developmental goals. At the beginning of the millennium, global leaders started working to achieve eight millennial developmental goals (MDGs).

In addition to achievements in access to drinking water, universal primary education, child and maternal health, gender equality, and eliminating hunger, the MDG 2015 report underscores the urgency of the post-2015 development agenda.

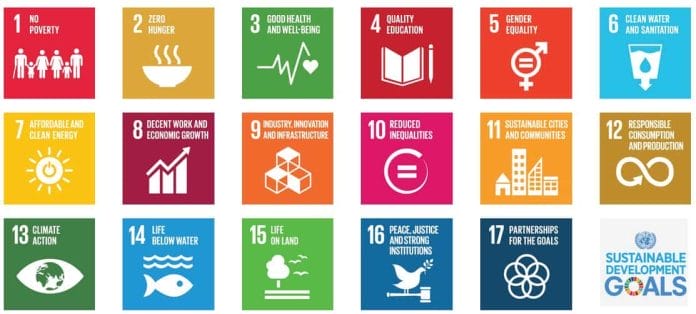

Hence, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) came into play as the core of the 2030 agenda with a blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet.

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development had an increased number of goals from eight goals in MDG to 17 goals in SDGs with more comprehensive targets. The SDGs were set with an urgent call for action by all countries – developed and developing – in a global partnership.

At the same time, SDGs’ achievements also need partnership between countries. In reality, SDGs cannot be achieved by any agency or a country that works in silo. Furthermore, in some cases, there is a dependency on achieving a target of one SDG on that of a different SDG.

Indeed, the SDG blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet is comprehensive enough. Yet, one important current global public concern namely the psychological health of adolescence, adults, and the aged population seem to escape a direct reference in SDGs. Which on the other hand, might need more weightage to be dealt with in the post-pandemic era.

Lack of psychological well-being has become a global phenomenon which became worse during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. The severity of this health concern in the post-pandemic era was unforeseen in 2015. Hence perhaps has not been identified as an independent target in SDG 3 or any other SDGs that were set in 2015.

SDG 3 addressing health and wellbeing aims to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all ages.

Rightly so, SDG 3 set nine targets: maternal mortality, neonatal and child mortality, infectious diseases, noncommunicable diseases, substance abuse, road traffic, sexual and reproductive health, universal health coverage, and environmental health.

According to the WHO Report 1998, the number of persons aged 65 years and above was about 390 million and was predicted to be 800 million by 2025. The same age group of population as of now has reached about a billion. A further prediction on the number of persons aged 80 years or over is projected to triple, from 143 million in 2019 to 426 million in 2050.

Taken together, an aged population will be a major concern in the future and that is inevitable due to the demographic transition towards longer lives and smaller families.

The aged population is not entirely left behind in SDGs. The World Social Report 2023 entitled, ‘Leaving no one behind in an aging world,’ by the UN Department for Economic and Social Affairs recalls that the 2030 Agenda aims to leave no one behind, particularly the most vulnerable people, including those at older ages. Nevertheless, the psychological well-being of elderly populations is far from a satisfactory level.

On one hand, we are expecting a shift away from a focus on economic value towards a human-centric society, where societal value and well-being remain at the core of IR 5.0. On the other hand, there is a decline in the importance of family-based societal structure. Over the past half-century, negative changes in family systems that pervaded the Western world are now spreading across the globe.

It is undeniable that family bonding works as the nucleus of a human-centric society. A lack of a proper and responsible family structure can gradually decompose the value of human interactions, hence a human-centric society where the elderly population in particular would be left mute in their lonely wilderness.

Family well-being has a few indirect references across the 2030 SDG agenda such as ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being for all at all ages or promoting shared responsibility within the household and the family as nationally appropriate. Again, reducing the global suicide rate that falls under SDG3.4.2 addresses promoting mental health and well-being. In addition, violence against women and girls is also a target for SDG 5.

Despite the differences in marital laws and practices, core family values of love, care, and protection as well as shared responsibilities are universal. Irrespective of social or cultural identity, family relationship is an inevitable contributing factor to psychological well-being.

Given the gravity and the spread of the concern of the aged population, as well as the concerns for psychological wellbeing for adolescents and adults global leaders might want to come up with specific targets and strategies to encourage future generations for a family and human-centric mindset.

Therefore, a family or human-centric society and psychological well-being deserve to be a primary target for holistic peace and prosperity of people and the planet.

The author is the Associate Dean (Continuing Education), Faculty of Dentistry, and Associate Member, UM LEAD, Universiti Malaya.